An In-depth Review of the Learning How to Learn Course on Coursera

If you plan on learning anything new, don't start until you've learned how to learn.

If you could have any superpower, what would it be?

Flying?

Invisibility?

Super strength?

When I was younger my answer was always ‘I’d have the superpower to use any superpower.’ The equivalent of wishing for more wishes when a genie appears.

Now if you asked me again, I’d tweak my answer.

‘I’d have the superpower to learn anything.’

Similar but not as much of a cop-out.

But why bother having to learn something if you had the choice for any superpower, why not go straight to knowing everything?

Because learning is the fun part. Knowing everything already would be a boring life. Have you ever seen how a 4-year-old walks into a park? Now compare that to a 40-year-old.

If you can learn how to learn, you can apply it to any other skill. Want to learn programming? Apply your ability to learn. Want to learn Chinese? Apply your ability to learn.

To improve my ability to learn, I went through the Learning How to Learn Course on Coursera. It’s one of the most popular online courses of all time. And I can see why.

It’s taught in a simple and easy to understand manner. The concepts are applicable immediately. Even throughout the course, as you learn something in part 1, it resurfaces in part 2, 3 and 4, reinforcing the new information.

If you’ve seen the course before and are thinking about signing up, close this article and do it now, it’s worth it.

Otherwise, keep reading for a non-exhaustive list of some of my favourite takeaways.

Part 1 — What is learning?

Focused and Diffused thinking

How do you answer such a question? What is learning?

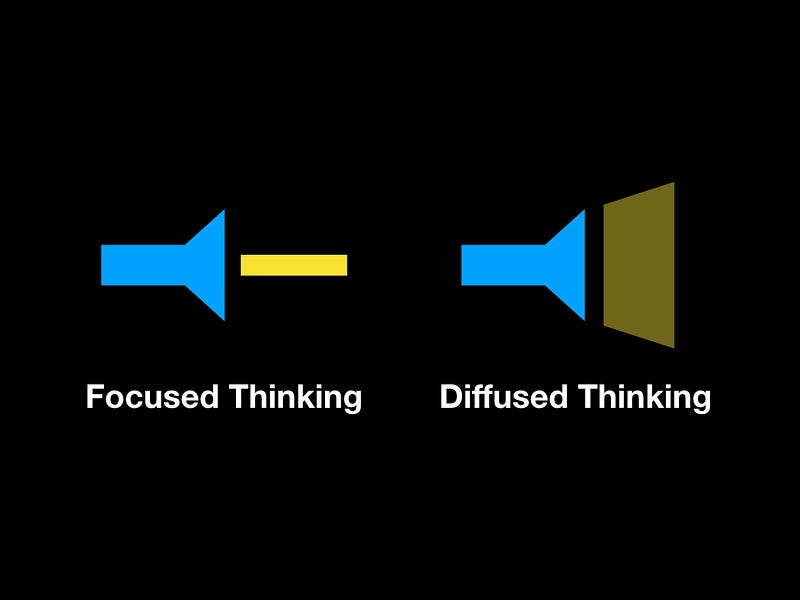

The course breaks it down with the combination of two kinds of thinking, focused and diffused.

Focused thinking involves working on a singular task. For example, reading this post. You’re devoting concentration to figuring out what the words on the screen mean.

Diffused thinking happens when you’re not focused on anything. You’ve probably experienced this on a walk through nature or when you’re laying in bed about to go to sleep. No thoughts but at the same time, all of the thoughts.

Learning happens at the crossover of these two kinds of thinking.

You focus on something intently for a period of time and then take a break and let your thoughts diffuse.

How often have you been stuck on a problem and then thought of answer in the shower?

This is an example of the two kinds of thinking at work. It doesn’t always happen consciously either.

Have you ever not known what step to take next on an assignment, left it overnight, come back and saw the solution immediately?

If you want to learn something, it’s important to take advantage of the two kinds of thinking. Combine intense periods of focus with intense periods of nothing.

After studying, take a walk, have a nap or sit around and do nothing. And don’t feel bad for it. You’re giving yourself the best opportunity to let the diffused mind do its thing.

Procrastination and how to combat it

You’re working a problem. You reach a difficult point. It’s uncomfortable to keep going so you start to feel unhappy. To fix this feeling, you seek something pleasurable. You open another tab, Facebook. You see the red notifications and click them. It feels good to have someone connecting with you. You see Sarah has invited you to her birthday. You look at the invites list, Gary is there. Gary is there. You’re not the biggest fan of Gary. Back in middle school, he was a prick. ‘Hey bro!’ he’d yell as he smacked you on the back. Hard. A bit more scrolling. Some advertisement for new shoes. The same ones you saw yesterday. They look real nice, black with orange. ‘I’m going to order them,’ you think.

You look down at your notes. You forget where you were up to.

What the hell just happened?

You were working on a problem. And you reached a difficult point. It was uncomfortable and you started to feel unhappy. You sought out something pleasurable. It worked. But only temporarily. Now you’re back to where you were and you’re even more upset at the fact you got distracted.

So how do you fix it?

The course suggests using the Pomodoro technique. I can vouch for this one.

It’s simple.

You set a timer and do nothing except what you wanted to work on for the duration. Even if it gets difficult, you keep working on it until the timer is done.

A typical Pomodoro timer is 25-minutes with a 5-minute break afterwards. During the break, you can do whatever you want before starting another 25-minute session.

But you can use any combination of working/break time.

For example, to complete this course, I used 1-hour Pomodoro timers with a 15–30-minute break in between.

1-hour studying.

15-minute break.

1-hour studying.

15-minute break.

1-hour studying.

30-minute break.

1-hour studying.

If 25-minutes is too long, start with 10 and make your way up.

Why is doing this valuable?

Because you can’t control whether or not you solve every problem which arises before the end of a days work.

But you can control how much time and effort you put in.

Can control: 4-hours of focused work in a day.

Can’t control: solving every assignment question in a day.

Sleep your way to better learning

We’ve talked about focused and diffused thinking. Sleep is perhaps the best way to engage unconscious diffused thinking.

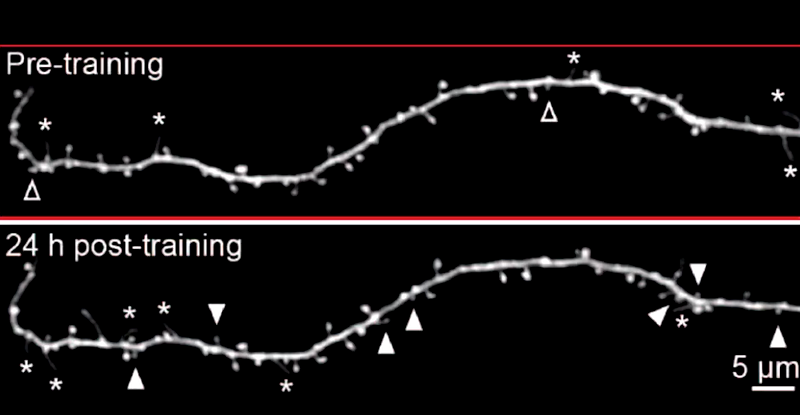

Being in focused mode is to brain cells what lifting weights is to muscles. You’re breaking them down.

Sleep provides an opportunity for them to repaired and for new connections to be formed.

There’s a reason famous thinkers like Einstein and Salvatore Dali would sleep for 10-hours at a time and tap multiple naps a day.

They knew it was vital for their brain to clear out toxins built up during the day which prevented engaging the focused mind.

The next time you feel like pulling an all-nighter and studying, you’d probably be better off getting a good night sleep and resuming the next day.

Spaced repetition, a little every day

Jerry Seinfeld writes jokes every day. He has a calendar on his wall and every day he writes jokes, he marks an X on it. Because he writes them every day if you looked the calendar you’d see a chain of X’s.

Once the chain has started, all he has to do is keep it going.

This technique is not only good for writing jokes. It can be used for learning too.

In the Learning How to Learn course, they refer to a similar concept called spaced repetition.

Spaced repetition involves practising something in small timeframes and as you get better at it, increasing the amount of time between each timeframe.

For example, when starting to learn Chinese, you might practice a single word every day for a week until you’re good at it. Then after the first week, you practice it twice a week. Then twice a month. Then once every two months. Eventually, it will be cemented in your mind.

The best learning happens when you combine these two concepts. Don’t break the chain by practising a little every day and incorporate spaced repetition by going over the difficult stuff more often.

To begin with, you could set yourself a goal of one Pomodoro a day on a given topic. After a week, you would’ve spent 3-hours on it. And after a year, you’ll have amassed over 150-hours. Not bad for only 25-minutes per day.Bonus: A great tool for spaced repetition is the flash card software Anki and for not breaking the chain, I recommend the Don’t Break the Chain poster from the writer’s store.

Part 2 — Chunking

Part 2 of the course introduces chunking. Multiple neurons firing together are considered a chunk. And chunking is the process of calling upon these regions in a way which they work together.

Why is this helpful?

Because when multiple chunks of neurons fire together, the brain can work more efficiently.

How do you form a chunk?

A chunk is formed by first grasping an understanding of a major concept and then figuring out where to use it.

If you were starting to learn programming, it would be unwise to try and learn an entire language off by heart. Instead, you might start with a single concept, let’s say loops. You don’t need to understand the language inside and out to know where to use loops. Instead, when you come across a problem which requires a loop, you can call upon the loops chunk in your brain and fill in the other pieces of the puzzle as you need.

Deliberate practice: do the hard thing

Forming a chunk is hard. First of all, what are the important concepts to learn? Second, where should you apply them?

This is exactly why you should spend time and effort trying to create them. Instead of learning every intricate detail, seek out what the major concepts are. Figure out how to apply them by testing yourself. Work through example problems.

The process of doing the hard thing is called deliberate practice. Spending more time on the things you find more difficult is how an average mind becomes a great mind.

Einstellung — don’t be held back by old thoughts

Dr Barbara Oakley introduces Einstellung as a German word for mindset.

But the meaning is deeper than a single word translation.

Every year you upgrade your smartphone’s software. A whole set of new features arrive along with several performance improvements.

When was the last time your way of thinking had a software upgrade?

Einstellung’s deeper meaning describes an older way of thinking holding back a newer, better way of thinking.

The danger of becoming an expert in something is losing the ability to think like an amateur. You get so good at the way that’s always worked, you become blind to the new.

If you’re learning something new, especially if it’s the first time in a while, it’s important to be mindful of Einstellung. Have an open mind and don’t be afraid of asking the stupid questions. After all, the only stupid question is the one that doesn’t get asked.

Recall — what did you just learn?

Out of what you’ve read so far, what has stood out the most?

Don’t scroll back up. Put the article down and think for a second.

How would you describe it to someone else?

It doesn’t have to be perfect, do it in your own words.

Doing this is called recall. Bringing the information you’ve just learned back to your mind without looking back at it.

You can do it with any topic. Reading a book? When you’re finished, put it down and describe your favourite parts in a few sentences.

Finished an online course? Write an article about your favourite topics without going back through the course. Sound familiar?

Practising recall is valuable because it avoids the illusion of competence. Rereading the same thing over and over again can give you an illusion of understanding it. But recalling it and reproducing the information in your own words is a way to figure out which parts you know and which parts you don’t.

Part 3 — Procrastination & Memory

The Habit Zombie

How hard do you have to think about making coffee in the morning at your house?

Not very much. So little, your half asleep zombie mode body can fumble around in the kitchen with boiling water and still manage to not get burned.

How?

Because you’ve done it enough it’s become a habit. It’s the same with getting dressed or brushing your teeth. These things you can do on autopilot.

Where do habits come into to learning?

The thing about habits is that almost anything can be turned into a habit. Including procrastination.

Above we talked about combating procrastination with a timer. But how do you approach from a habit standpoint?

Part 3 of the Learning How to Learn course breaks habits into four parts.

- The cue — an event which triggers the next three steps. We’ll use the example of your phone going off.

- The routine — what happens when you’re triggered by the cue. In the phone example, you check your phone.

- The reward — the good feeling you get for following the routine. Checking your phone, you see the message from a friend, this feels good.

- The belief — the thoughts which reinforce the habit. You realise you checked your phone, now you think to yourself, ‘I’m a person who easily gets distracted.’

How could you fix this?

You only have to remove one of the four steps for the rest to crumble.

Can you figure out what it is?

The cue.

What would happen if your phone was in another room? Or turned off?

The cue would never happen, neither would the subsequent steps.

The technique of removing the cue doesn’t only work for procrastination. It can work for other habits too. It also works in reverse. If you want to create a good habit. Consider the four steps.

To make a good habit, create a cue, make a routine around it, give yourself a reward if you follow through and you’ll start forming a belief about you being the type of person who has the good habit.

The dictionary isn’t the only place product comes after process

Thinking about the outcome of your learning is the quickest way to get discouraged about it.

Why?

Because there is no end. Learning is a lifelong journey.

No one in history has ever said, ‘I’ve learned enough.’

And if they have, they were lying.

I’ve been speaking English since I was young. Even after 25-years of speech, I still make mistakes, daily. But would getting upset at where my level of English is at be helpful? No.

What could I do?

I could accept that knowing everything about speech and the English language is impossible. And instead, focus on the process of speaking.

This principle can be related to anything you’re trying to learn or create.

If you want to get better at writing, the end product could be a bestselling book. But if I told you to go and write a bestselling book, what would you write?

Worrying about what a bestselling book would have in it would consume you. It’s far more useful to focus on the process, to write something every day.

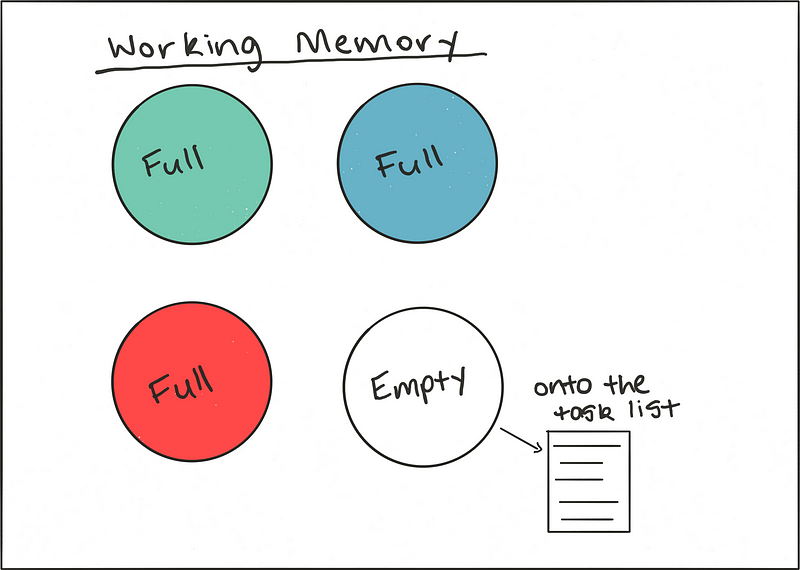

Free up your working memory and set a task list the night before

Dr Oakley says we’ve got space for about four things in working memory. But if you’re like me, it’s probably closer to one.

Some of the people I work with have three monitors with things happening on all of them, I’m not sure how they do it. I stick to one and push it to two when a task requires it.

If I had a third monitor it would be the A5 notepad I carry around everywhere. It’s my personal assistant. Every morning, I write down a list of half a dozen or so things I want to get done during the day. Sometimes I write the same list on the whiteboard in my room to really clear out my brain.

Even when I’m in the middle of a focused session, 12 minutes into a Pomodoro, things still come out of nowhere. Rather than stop the Pomodoro, the thought gets trapped on the paper. Working memory free’d up.

The course recommends creating a list of things the night before but I’m a fan of first thing in the morning as well. Putting things down means they’re out of your head and you can devote all of your brainpower to focused thinking rather than worrying about what it was you had to do later.

Don’t forget to add a finishing time. The time of day you’ll call it quits.

Why?

Because having a cutoff time means you’ve got a set timeframe to complete the tasks in. A set timeframe creates another reason to avoid procrastination.

And having a cutoff time for focused work means you’ll be giving your brain time to switch to diffused thinking. Who knows. That problem you couldn’t solve at 4:37 may solve itself whilst you’re in the shower at 8:13.

Part 4 — Renaissance learning & unlocking your potential

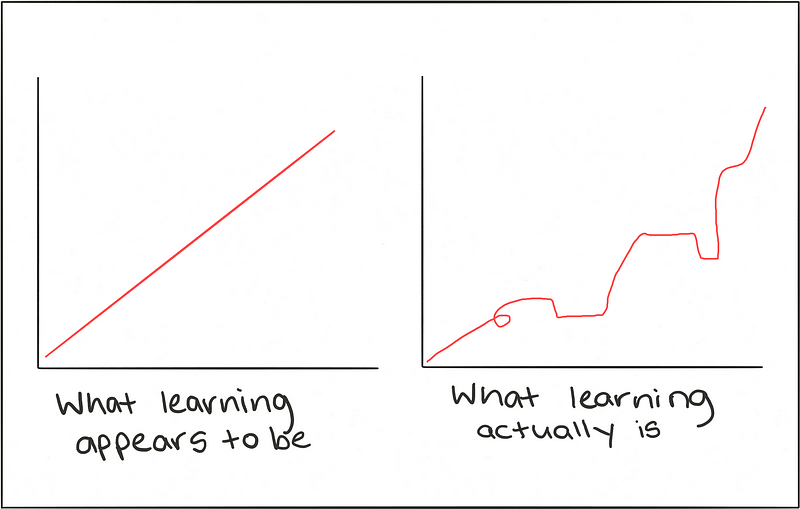

Learning doesn’t happen in a straight line

You could study all weekend and go back to work on Monday and no one would know.

You could work on a problem all week and by the end of the week feel like you’re worse off than you started.

Dr Sejnowski knows this. And emphasises learning doesn’t happen linearly.

Learning tough skills doesn’t happen over the course of days or weeks or months. Years is the right timeframe for most things.

I wanted to know how quickly how quickly I could learn all of the math concepts behind machine learning: calculus, linear algebra, probability. I found a question on Quora about it.

A person who had been studying machine learning for 30-years replied with, ‘Decades.’ And then explained how he was still discovering new things.

I was impatient. I was focusing on product rather than process.

Learning looks more like a broken staircase than a straight line.

Charles Darwin was a college dropout

How do you go from medical school dropout to discovering the theory of evolution?

Easy. You be Charles Darwin.

But what if you’re not Charles Darwin?

Not to worry, not everyone is Charles Darwin.

There will never be another Charles Darwin. History repeats, but never perfectly. It’s better to think of it as a rhyme. History rhymes with the future.

Charles Darwin dropped out of medical school much to the disappointment of his family of physicians. He then travelled the world as a naturist.

Years went on but one thing never changed, he kept looking at things in nature with a child-like mind.

He’d take walks multiple times per day in between periods of study. Focused mind and diffused mind.

Take any introduction to biology course and you’ll know what happened next.

I’ve condensed a story of decades into sentences but the point is everyone has to start somewhere.

The first year you learn something new you suck. The second year you suck even more because you realise how much you don’t know.

There’s no need to envy those who seem to know what they’re doing. Every genius starts somewhere.

‘He who says he can and he who says he can’t are usually right’

The course credits Henry Ford as saying the above. But the internet is telling me it’s from Confucius.

It doesn’t matter. Whoever said it was also right.

If you believe you can’t learn something, you’re right.

If you believe you can learn something, you’re right.

Dr Oakley was a linguist during her twenties. She didn’t like math. So how did she become an engineering professor?

By changing her belief in what she could learn.

I used to tell myself, ‘I’ll never be the best engineer.’

I said it to someone at a meetup. They replied, ‘not with that attitude.’ A simple yet profound statement. All the best ones are.

Whatever it is you decide to learn, it all starts with the story you tell yourself. Pretend you’re the hero in the story of your own learning journey. Challenges will arise. It’s inevitable. But how does the hero deal with them? You decide.

Learning: the ultimate meta-skill

Taking responsibility for your learning is one of the most important undertakings you can manage.

Learning is the ultimate meta-skill as it can be applied to any other skill. So if you want to improve your ability to do anything, learning how to learn is something you should dedicate time to.

The things I’ve mentioned in this article are only scratching the surface of what’s available in the Learning How to Learn course. I’ve left out exercise, learning with others, studying in different locations. But you can imagine the benefits these have.

If you want to dig deeper, I highly recommend checking out the full Learning How to Learn course. I paid for the certificate but it’s not needed. You can access all the materials for free. However, I find I take things more seriously when I pay for them. And the information in this course is worth paying for.

If you’re not embarrassed by who you were last year, you’re not learning enough. — Alain de Botton

Keep learning.